Renting research revisited - Part 1

04/01/2020 • Robert Mowbray

Some twenty to thirty years ago I wrote two theses on the private rental market in New South Wales. They both documented residential tenancy law reform and followed the report on ‘Law and Poverty’ by the Commonwealth Government’s Commission of Inquiry into Poverty, released in October 1975. This Inquiry was a major fillip for residential tenancy law reform across Australia. It argued (p 59) that landlord and tenant legislation across Australia was in many respects unfair, particularly for low-income and disadvantaged tenants. A major report to this Inquiry, prepared by Adrian Bradbrook (entitled ‘Poverty and the Residential Landlord-Tenant Relationship’), described the law at the time as a ‘scandal’ and concluded that there were grave deficiencies which needed to be remedied in the interest of tenants.

This house in Newtown was the home of a 94 year-old tenant who had lived in this same house for 70 years. Her succession of landlords all flatly refused to do repairs.

In a two-part series, I revisit these theses.

The first was a Masters thesis examining the period up to December 1987:

- ‘Towards a Better Understanding of Private Renting in NSW - an Exploratory Study’. This was a thesis for the degree of Master of Town and Country Planning in the Faculty of Architecture, University of Sydney in December 1987.

Here’s an extract from the ‘Abstract’:

Housing programs in Australia since the Second World War have increased inequalities in access to housing amongst households. This is because such policies have primarily focused on tenure – promoting home ownership, restricting the growth of public housing and neglecting private renters. Over the last fifteen years significant structural changes have taken place in the private rental market in New South Wales. The types of landlords who dominate have changed. The effect of this is to reduce the attractiveness of private renting from the tenant’s perspective. Yet tenants belong increasingly to marginalised groups where poverty is a major issue. ... [T]he government has been reluctant to enact significant reform. This reluctance is explained in terms of the structural changes.

I conclude that private rental housing is a most inequitable form of tenure for low income households. My conclusion is reached on the basis of existing sources of information. The paucity of existing data makes it imperative to explore other sources. A study of Rental Bond Board data highlights its potential for improving knowledge of rental housing stock in New South Wales, especially if linked to other data bases ... enable[ing] policy makers to predict the impact of changes in fiscal and housing policies on supply.

The second was a PhD thesis. It took a sample of rental properties for which rental bonds were held by the Rental Bond Board and linked this data to other data sources, including the Land Titles Office, and the findings of a survey that I administered. I followed these rental properties over 10 years. My thesis uses the findings of this longitudinal study to explain the reluctance by governments to introduce far reaching reform. It was called:

- ‘The Nature of Contemporary Landlordism in New South Wales: Implications for Tenants' Rights’. This was a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Architecture, University of Sydney in March 1996. Available here.

Here’s the ‘Abstract’ from my PhD thesis (p i):

Comprehensive residential tenancy law reform in New South Wales has not provided security of tenure for tenants. A critical review of the reform legislation concludes that tenants' ability to make full use of its provisions is undermined by this omission: indeed, the evidence points to landlords being the major beneficiaries of the legislation. This thesis seeks to explain the legislative limits of tenants' rights in New South Wales through a better understanding of contemporary landlords. A longitudinal study of a sample of properties in the private residential rental market was undertaken through collecting information from land-based data sources and landlords. It found that there are different types of landlords who behave differently in the market place. Between 40 and 50 per cent of all rental stock in New South Wales is held by landlords who own a single property. A sizeable proportion of these landlords are temporary landlords who control in excess of one third of the rental stock. Just over half of the rental stock is controlled by another type of landlord (a particular category of investor). Although their motivations are different, the common thread which binds these two types of landlords who dominate the market is the need to obtain vacant possession of their premises with a minimum of effort. This is because the private rental sector has become enmeshed in the predominantly owner-occupier market. Indeed, reference is made to commentators who argue that the resilience of the private rental market in Australia, compared to overseas countries, is largely due to a sympathetic taxation regime which has encouraged investment in housing stock. Accordingly, the granting of security of tenure would be a barrier to landlords recovering their premises for their own occupation or liquidating their investments in the market. Thus, it is argued that the nature of contemporary landlordism in New South Wales acts in general against the best interests of tenants and in particular against their need for security of tenure. An important implication which flows from this study is that any shift in government policy to reduce the role of public housing and place a greater reliance on the private rental market to house low-income people is misplaced.

Have my findings dated? I think not. They still are very relevant today, as evidenced in some more recent reports which I discuss in Parts 1 and 2 of this blog.

1. Private rental and home ownership markets are totally enmeshed ...

My PhD thesis tells this story. Here, I followed over 10 years the histories of 733 properties that, at the starting date for my study (31 December 1983), were all in the private rental market. My results indicate a number of important characteristics of the housing market in New South Wales at the time of the study:

• Half of the properties in the private rental market can be expected to be sold in an 8 year period and the turnover rate is greater where properties have been owned for shorter periods of time.

• Half of the properties in the private rental market can be expected to be lost to the private rental market after 10 years. Although a proportion of those sold return, a proportion of those not sold drop out.

I quote here (pp 178 to 180):

Whether premises remained in the private rental market

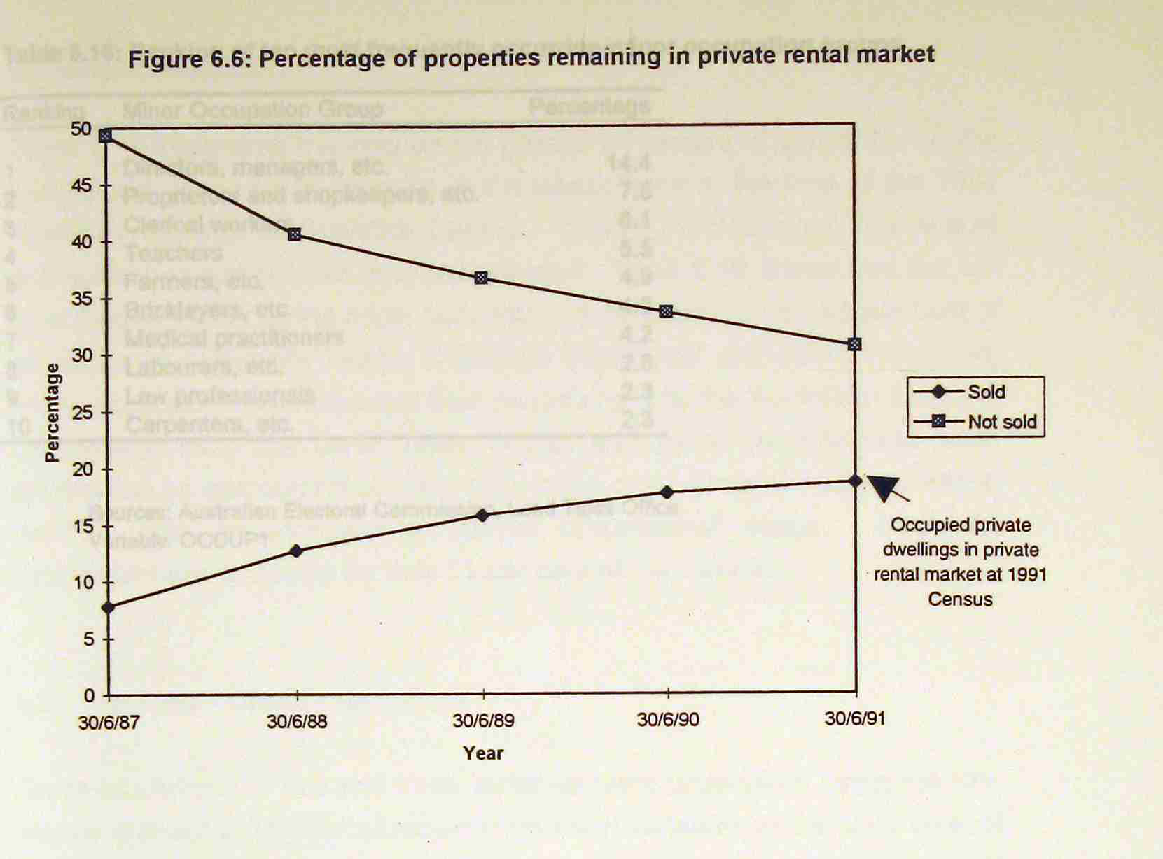

Table 6.13 shows that just under six out of ten properties remained in the private rental market after 3.5 years. This figure reduced to one half of all properties after 10 years. Table 6.14 provides percentage figures comparing properties which had been sold with those which had not been sold. This is represented in Figure 6.6 [reproduced below], which highlights two trends: firstly, an increasing proportion returned to the private rental market over time even though sold and, secondly, a proportion dropped out of the private rental market over time even though never sold.

This result indicates an important characteristic of the contemporary housing market in New South Wales - housing stock moves between the tenures of private rental and owner-occupation. Transferability between tenures occurs either through the sale of the property or through the purposes to which the owners put the property -- as a temporary or permanent form of investment or use for their own accommodation. If the private rental and owner-occupier markets are totally enmeshed, then it could be postulated that over time the percentage of properties in the sample which are in the private rental market at a point in time would tend towards the figure for the percentage of occupied private rental dwellings across the whole market. The properties in this sample were drawn from a simple random sample of all Rental Bond Board lodgements across New South Wales. The proportion of occupied private dwellings (excluding "caravans etc in caravan parks") in New South Wales at the time of the 1991 Australian Bureau of Statistics Census was 19.2 per cent where "Landlord Type" is "Rented:Other" (Australian Bureau of Statistics 1994c, Time Series Profile Table 28). Table 6.14 shows a definite tend towards this percentage (19.2 per cent) with the figure reaching 18.6 per cent after 8 years. On the other hand, it could be postulated that the percentage of properties remaining in the private rental market where the properties were not sold would decrease, but always remain well above the Census figure. This is because a significant proportion would remain in the private rental market, either for investment purposes or until a change of land use occurred. Table 6.14 also demonstrates this.

The finding that private rental and home ownership markets are totally enmeshed is a theme picked up in contemporary writings. Chris Martin (in Paragraph ‘2.1 Rental property ownership structure and security’, Property Law Review, Vol. 7 Pt 3, November 2018) writes:

Australia’s relative lack of sector differentiation raises the prospect of properties readily transferring between sectors. There is evidence that rental properties do in fact frequently exit the sector: in a study by Yates and Wood, 40 per cent of dwellings rented privately in Sydney in 1991 had by 2001 left the rental sector - presumably to be used as owner-occupied housing, ...

Analysis by Wood and Ong of a sample taken over the period 2001-06 shows 25 per cent of landlords exited the market within their first year; a minority (41 per cent) remained in the market continuously for five or more years.

2. Who are the landlords …

I discuss landlords of residential rental properties across NSW in the 1980s and 1990s in Chapters 6 and 7 of my PhD thesis (pp 191-192, 247-252). These figures are obviously aged now, but give an insight into changes of our rental system.

For landlords who responded to my questionnaire, 32 per cent of premises were owned by individuals, 46 per cent by partnerships (two or more individuals, or businesses), 17 per cent by companies and 5 per cent by others (including government authorities and churches) (see Table 2 in Appendix 23, p 369).

I found that a typical owner of residential rental property is either an individual or two or more individuals from a professional, managerial or sales occupation who probably lives in the central metropolitan area of Sydney, and acquires a house or strata titled unit in the same region as where they live. This last trend is strongest if they reside in a country region).

I found that the landlord has probably owned the property for less than 5 years and will probably dispose of it in a period of up to 8 years. However, if that property has been owned for a long period of time, they are less inclined to sell it. Nevertheless, in some cases, they may remove it from the private rental market.

The above categorisation of landlords is referred to an institutional definition of landlord.

A more sophisticated understanding of landlords uses a typology of private of landlords, similar to that developed by Allen (1983), Paris (1984a, 1985a), Allen and McDowell (1989), Elton and Associates (1991). (Full references are shown in my Bibliography.) Here, classification of landlords is according to the ‘causal characteristics’ of landlords in the market place (p 41). Classification of landlords by ‘causal groupings’ (‘functional definition’) allows an estimate of the market share of each type of landlord. I developed the following typology of private landlords (Table 5.1, p 152):

Typology of private landlords

1. Temporary landlords: where the property was purchased for owner occupation but subsequently let, inherited, built for sale and let temporarily, purchased for conversion to non-residential use and let in the meanwhile, or purchased to provide accommodation for relatives; and in all of these cases the owner is none of a government body, council nor other body (other body excluding individual/s, business or company).

2. Investors - Type A: Where the owner is one or more individuals and either the property was purchased as part of a block of flats with the intention of converting the block to strata title and then selling the units or the owner built/contracted a builder to build in order to let as an investment; where the property was purchased to let as an investment and the owner purchased the property as long-term security or other (not short-term investment) and the property is managed by a real estate agent or other body; where the property was purchased to let as an investment and the owner purchased the property not as long-term security.

3. Investors - Type B: where the owner is a business or company and the property was purchased as part of a block of flats with the intention of converting the block to strata title and then selling the units; where the owner is a business or company and the owner built / contracted a builder to build in order to let as an investment.

4. Owner-managers: where the property was purchased to let as an investment and the owner purchased the property as long-term security or other (other not being short-term investment) and the property is managed by the owner.

5. Employer landlords: Where the property was purchased to provide accommodation for employees.

6. Other institutional landlords: where the owner is one of a government body, council or other (other body excluding individual/s, business or company) and the property was purchased for reasons other than to provide accommodation for employees.

My PhD found that investors (Type A) control around half and temporary landlords control somewhere in excess of one third of residential rental properties across New South Wales. The role of other types of landlords such as investors (Type B) and government instrumentalities was not insignificant as some held large holdings. (pp 203 -203) These figures exclude informal landlords because this study was unable to examine them, even though they were seen as of growing importance. At the time of my study their numbers, nationally, were estimated at 10 to 15 per cent of all landlords (Elton and Associates, 1991, pp 51-52).

Classification of landlords by ‘causal groupings’ is a useful tool for predicting responses to policy measures and changes in the investment environment. For example, a significant finding of my study (p 251) was that the types of landlords who dominate in the private rental market - investors (Type A) and temporary landlords - rank residential tenancy law reform low in factors considered when deciding ·to invest or disinvest. They place greater importance on taxation advantages. Also, temporary landlords leave the private rental market at a faster rate than other types of landlords.

If we fast forward to the present time, you will find expanded information on the types of landlords who now dominate the private rental market in the comprehensive discussion of 'Ownership of investment properties and holiday homes' on pages 73 to 75 of The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 14, 2016 :

A rise in the proportion of households owning non-home property between 2002 and 2014 is evident, with most of the increase occurring between 2002 and 2006. The proportion owning non-home property was 16.5% in 2002, 20.6% in 2006 and 21.0% in 2014. This is consistent with the finding in Chapter 5 of a decline in home-owner households—and hence an increase in renting. Data for 2006 to 2014 show ownership of holiday homes was 5.6% in 2006, 6.1% in 2010 and 5.7% in 2014, while ownership of investment housing was 12.3% in 2006, 12.2% in 2010 and 13.0% in 2014. Ownership of other non-home property declined slightly between 2006 and 2014, from 5.5% to 4.7%

Data on investment properties has been updated in the most recent data release (Release 18) and a discussion will be included in the HILDA Survey report available in late July 2020.

You will find a discussion of the players in property investment here and here and what a typical landlord looks like here. Key findings from these links, dated between 2016 and 2018, are: 2.03 million individuals making up 15.7% of all taxpayers invest in residential housing and, on average, each investor owns 1.28 investment properties; the greatest increase in volume of overall investors comes from individuals in the taxable income bracket of $80,001 to $180,000; more than one fifth of investors are now aged over 60 years, a share that will likely increase over time, and the vast majority of investors own only one or two properties … and the typical landlord is an owner occupier, at midlife, in a household with two incomes.

You will find figures current at 10 May 2019 on the number of people using negative gearing to invest in rental properties in the Tenants’ Union of NSW’s blog here. You also will find an analysis of Australian Taxation Office data in an article by Rachel Eddie and Craig Butt: ‘Who benefits most from negative gearing?’ here. These journalists draw from taxation statistics from 2016-17 which you will find here.

In Part 2 of this blog I will examine ‘3. And what motivates landlords?’ and ‘4. The state of residential tenancy law reform’.